Elizabeth Magill – ‘Headland’: A Printmaker’s Perspective

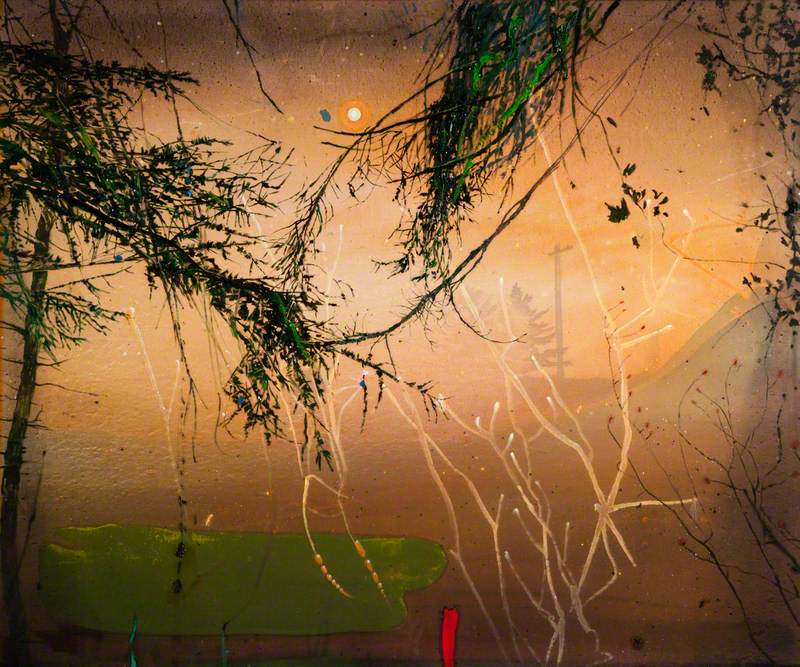

I first encountered the work of Elizabeth Magill in Belfast’s Ulster Museum, specifically through a painting entitled Chronicle of Orange (2008). In the work, plant forms and trees are bathed in a pool of orange urban streetlight. It had an immediate impact on me – perhaps because it seemed to tie together many of the things I was preoccupied with at the time: nature invading urban spaces, hidden and overlooked places, finding beauty in the mundane. I thought she did it so well I bought a copy of the museum’s catalogue so I would remember the painting.

Elizabeth Magill; Chronicle of Orange; National Museums Northern Ireland

10 years after that canvas was painted, in 2018, visitors to the same museum have the chance to see her new solo exhibition ‘Headland’ before it travels to Walsall.

Magill grew up in Northern Ireland (North Antrim) but lives and works in London. She began exhibiting in the mid-1980s. ‘Headland’, a show of ‘new and recent work’ comprises, with one or two exceptions, landscape paintings, of a more rural nature to the urban landscape of Chronicle of Orange. Some pieces include small figures. The figure in a landscape, and its association with notions of the sublime, have inspired (one assumes) the Caspar David Friedrich references in some commentaries on her work, a comparison she tries to resist. I find there is something of Peter Doig in her heightened colour palette and treatment of trees.

Worth noting are the captions which describe the works as ‘oil and silkscreen on canvas’. I could not help investigating each piece to see where the silkscreen ended and the painting began. These are large works, many close to two metres in either length or width (183 x 153cm is a common size). Working with screens of these dimensions is not easy, not least because of their bulk, but also in terms getting a decent image from screen to surface (in this case, canvas or paper). As a printmaker, you assume that the effort that goes into exposing a screen of that size (i.e. using a blown up photograph to create a stencil) means using it more than once. I do not know if silkscreen played any role in the making of Chronicle of Orange but being able to take in several of Magill’s works in the same room, as in the current ‘Headland’ show, makes it easier to pick out the recurring motifs i.e. the re-use of the same exposed screen in other pieces in the gallery space.

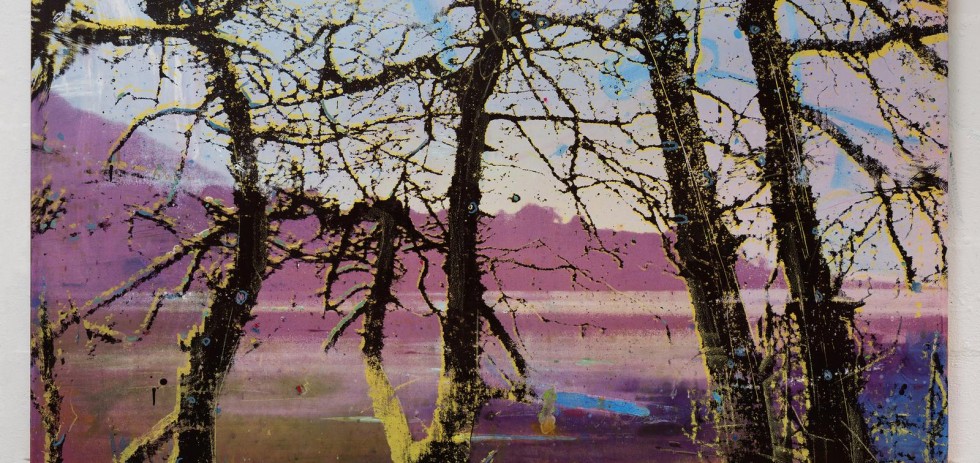

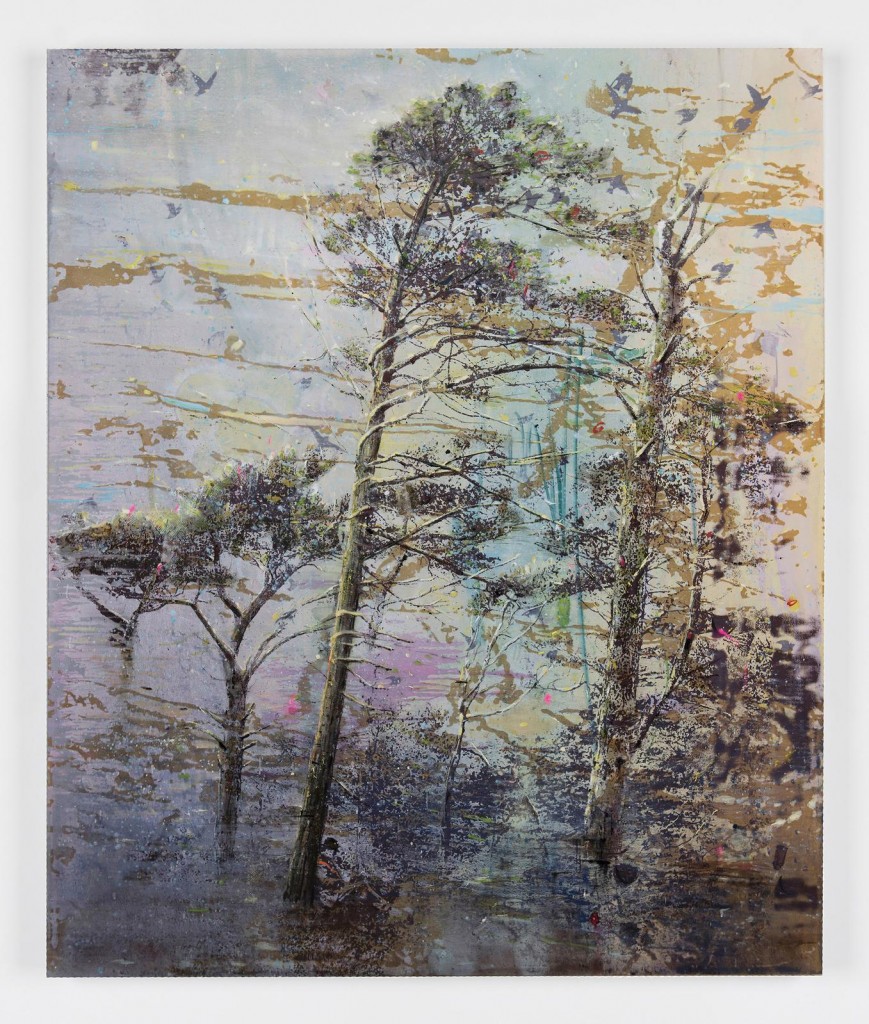

Elizabeth Magill, Still (1), 2017, oil and silkscreen on canvas, 183 x 153 cm / 72 x 60.2 in

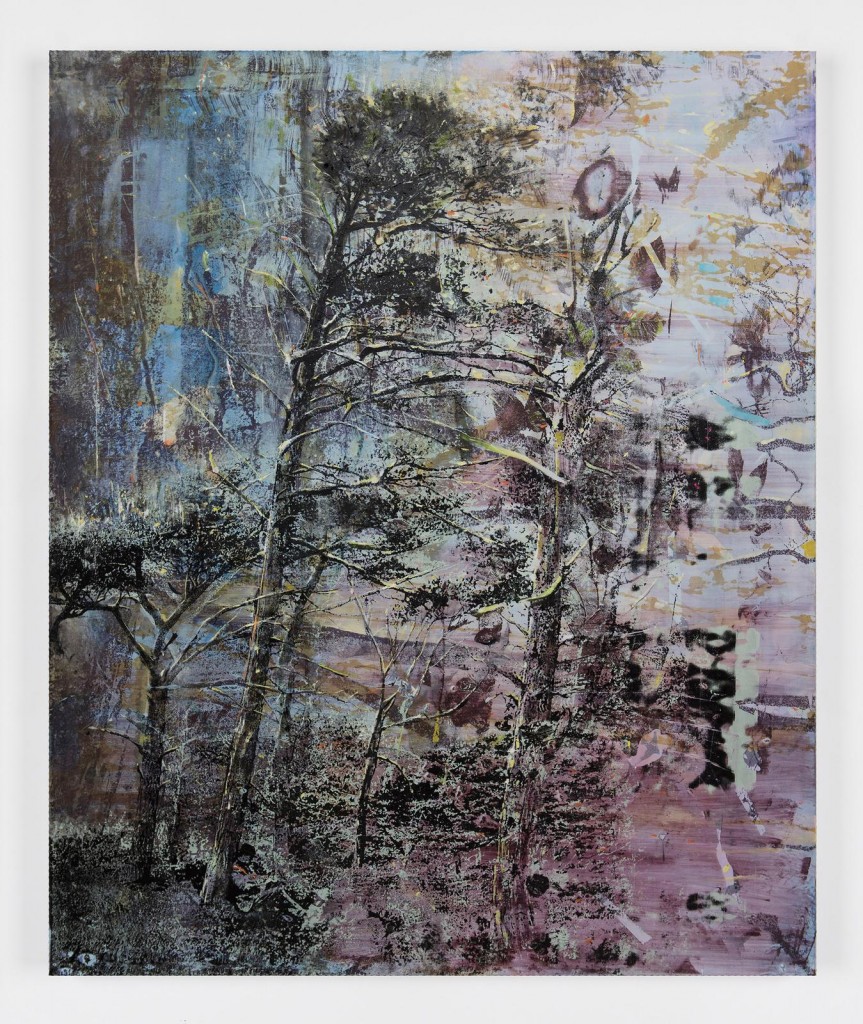

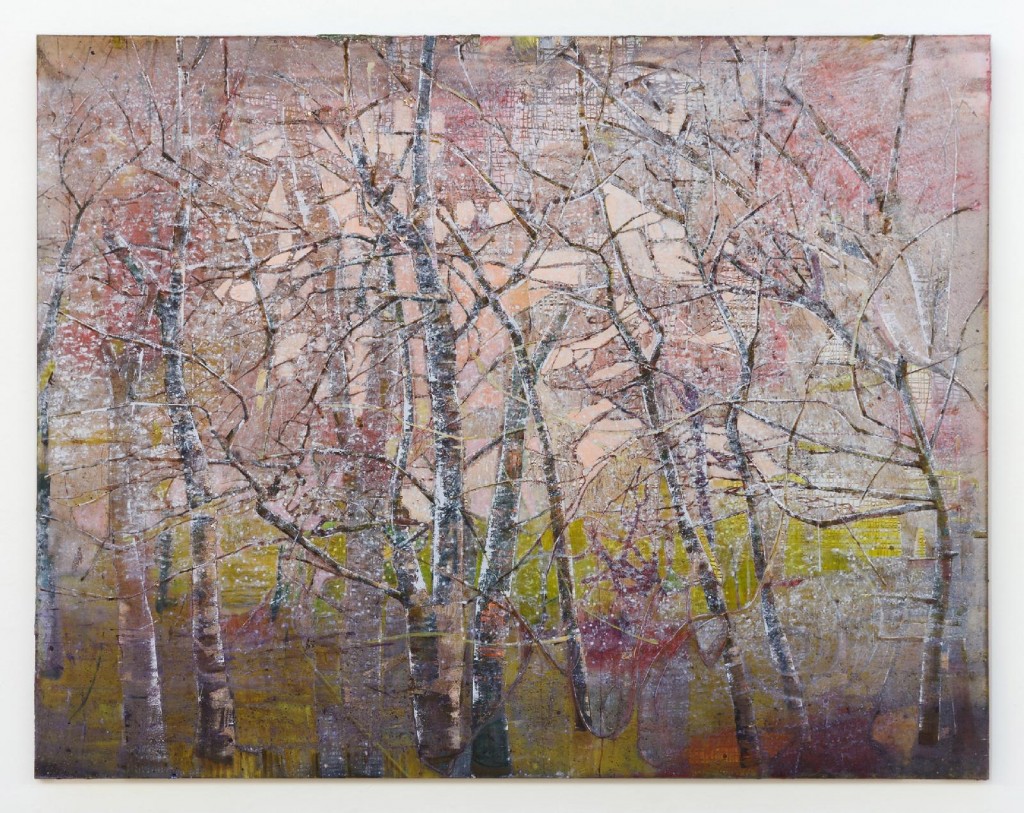

Elizabeth Magill, Still (2), 2017, oil and silkscreen on canvas, 183 x 153 cm / 72 x 60.2 in

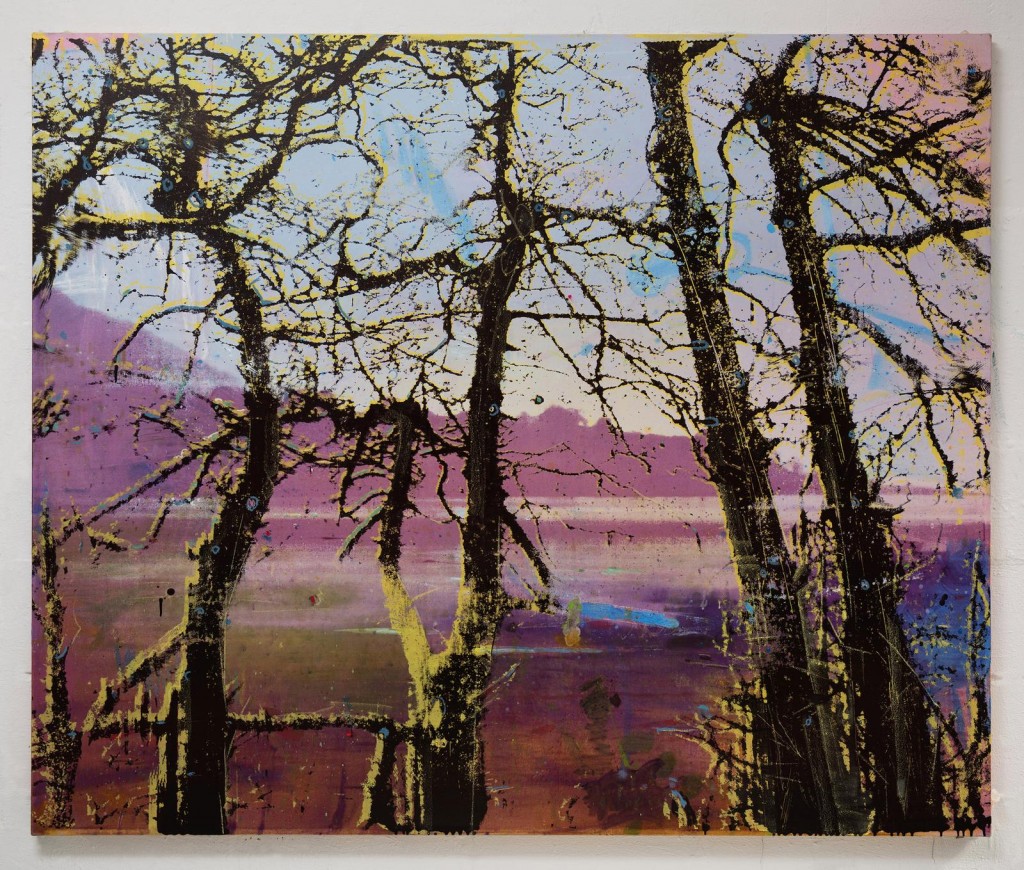

Elizabeth Magill, Headland (1), 2017, oil and screenprint on canvas, 153 x 183.5 cm / 60.2 x 72.2 in

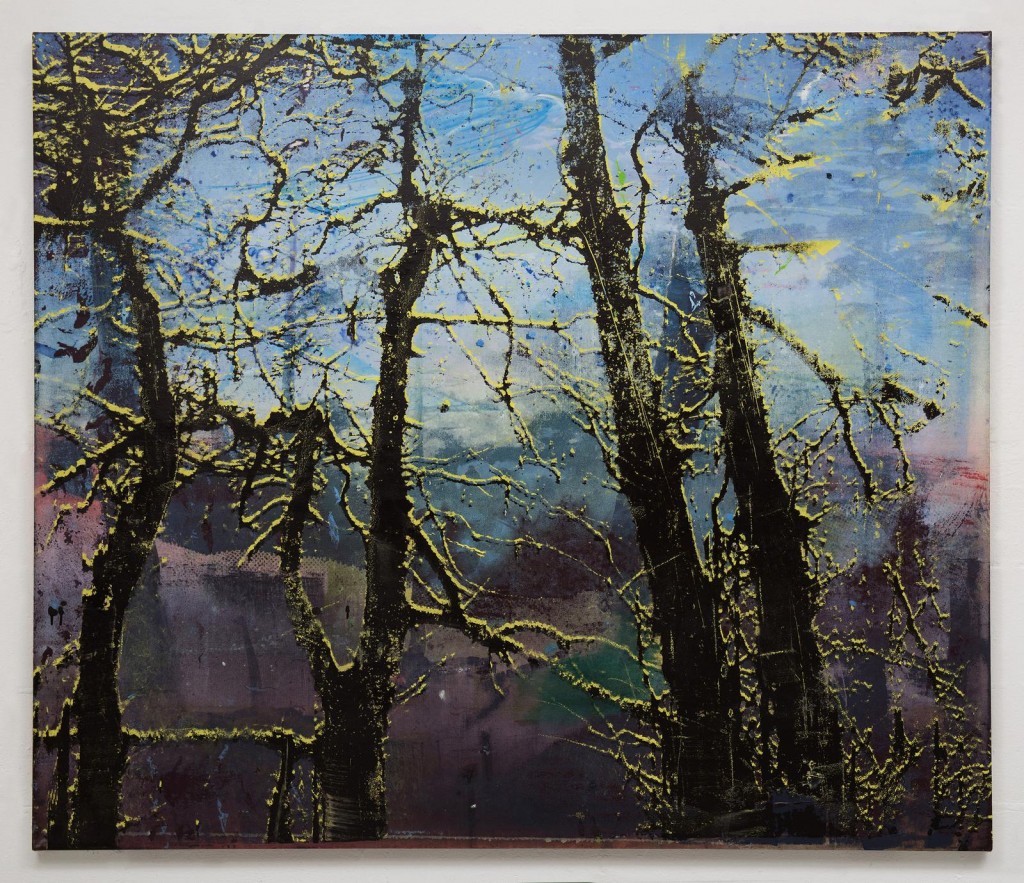

There are several examples: the branch forms in Of (2) (2017), re-appear in Unstill (2017), Red Bay (2016-17), and Wildlife (2017). A different sequence of trees appears in Neck (2017), Still (1) and Still (2) (all 2017) and yet another set features in Anterior (1) and Headland (1) (both 2017). What is remarkable is that these motifs are treated so differently – in terms of colour and a palette of dribbles and washes and speckles – that their re-use is not immediately apparent.

In this respect, i.e. the use of print techniques to create images on multiple canvases not to create a print edition, but rather to work in broad series, her approach recalls that of Philip Taaffe, however, beyond this observation the comparison ceases to be useful.

Elizabeth Magill, Anterior (1), 2017, oil and screenprint on canvas, 153 x 183 cm / 60.2 x 72 in

Artists as diverse as Picasso, Rembrandt, Käthe Kollwitz and Louise Bourgeois were prolific printmakers, yet the art itself seems underrepresented in our major institutions. I suspect there are several reasons for this, not least the care needed in storing, restoring, framing and exhibiting works on paper. Problematic also is the word used to describe the artefact itself, i.e. a ‘print’. Since the advent of mass production of imagery, from offset lithography to today’s digital reproductions, the term ‘print’ has become synonymous with reproductions of existing works of art rather than original works of art in themselves. People go to museum shops to get a postcard or ‘print’ of the painting they admired on the gallery wall. Even artists working in other media refer to ‘prints’ of their work, rather than reproductions (not to mention photographic and giclée prints as works of art). In short, it is understandable that the term ‘print’ is misused and misunderstood. Yet the printmaker might feel disappointed when established artists employ printmaking techniques but neglect to recognise this in captions or discussions on their art practice, preferring other terms such as ‘mixed media’ or ‘pigment on canvas’. Although I am acutely aware that printmakers (and perhaps ceramicists and film photographers) are obsessed with process and technique, refreshing here are Magill’s captions: ‘oil and screen-print on canvas’, ‘oil and silkscreen on canvas’, etc.’ It is a celebration of the medium by an established artist. A recent interview with Tracey Emin, a fan of the ‘magic and alchemy’ of printmaking, gives one further hope: “People used to undervalue works on paper, but that’s changing. What is wonderful about prints is that they are really accessible”.

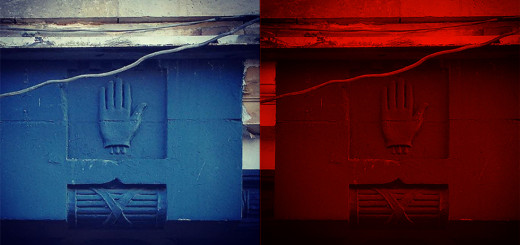

Printmaking processes are referenced other ways in Anterior (1) and Headland (1). In both works, the same silhouetted trees are printed in a light colour, a pale yellow, and then printed over in a darker colour, a deep brown, but slightly misaligned. The effect calls to mind misaligned registration in silkscreen printing (usually something one tries to avoid), yet in Magill’s case it is done on purpose and to great effect. Here, one experiences it as a kind of a penumbra, of light hitting a surface that has its back to you but the glint from the other side can still be seen. You sense her love of experimentation here and also in a series of smaller pieces which employ ‘oil and film’ on canvas.

Elizabeth Magill, Dendriform 10, 2012, oil on canvas, 214 x 277cm

And while there is repetition here, there are also singular pieces such as Dendriform 10 (2012) – at 214 x 277cm, the largest work in the current show. The painting features multiple overlapping trees in which background is as important as foreground, the gaps between branches almost treated like a mosaic. There’s a lovely waxy texture to the surface. It is reminiscent of Mondrian’s early abstractions of nature in which a tree becomes incrementally fragmented and reduced to elemental lines, a Cubist-inspired process of his own design which led ultimately to the austerity of De Stijl.

Piet Mondrian, Blossoming apple tree, 1912, oil on canvas, 78.5 x 107.5 cm

There is much to enjoy in this show, and repeated viewings bring rewards. Several pieces in one series reveal a sense of humour and vague political references, with a little Orangeman seated beneath a tree – Still (1). There is also a playfulness in the way that background elements will sometimes obscure those in the foreground. The mysterious Fishman (2014-15), and the Doig-like Irrawaddy (2017) are harder to read in terms of subject matter.

I am and remain an enormous fan of Magill’s work. ‘Headland’ ends this weekend – go see it while you still can.

All images courtesy of Elizabeth Magill, Kerlin Gallery (Dublin)