A Belfast Blog meets: Emma Jane Grey

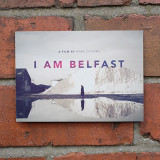

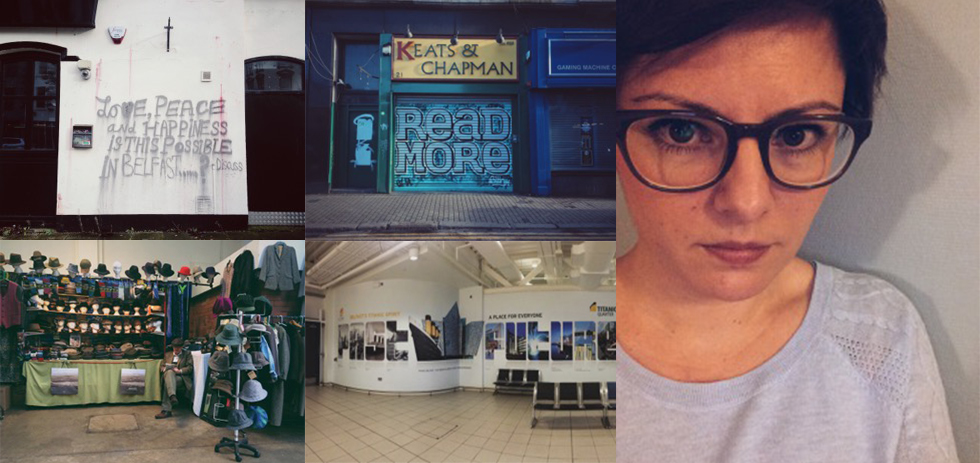

A Belfast Blog asked to speak to Emma Jane Grey who is in the process of completing a PhD at the University of Aberdeen entitled ‘Archival Amnesia: Memory and Culture in Post-Ceasefire Northern Ireland’. Emma’s research focusses on literature and visual art produced in Northern Ireland from 1994 to the present day, exploring how artistic production reflects upon, contests and subverts processes of selective forgetting and erasure prevalent within governmental and media accounts of ‘The Troubles’.

For this interview, A Belfast Blog asked Emma about her memories, insights and perspectives on Belfast and Northern Ireland. However, we hope that there will also be an opportunity, further down the line, to delve into deeper conversations about her work.

Emma, how would you describe Belfast, to someone who has never visited?

Someone who has never been to Belfast will undoubtedly have a lot of preconceived ideas about what Belfast is like because of ‘the Troubles’[1] and ongoing sectarianism: phrases like ‘bomb scares’, ‘peace walls’, ‘interface zones’, ‘flag disputes’ and a seemingly unending number of acronyms such as UDA, UVF, IRA, and INLA. This was brilliantly parodied by Robert McLiam Wilson in his 1996 novel Eureka Street in which a new acronym, OTG, appears graffitied on walls. No one knows what it means and this sense of the unknown produces no end of anxiety for those behind the many known acronyms.

But Belfast is more than all these words. No city is one thing. There’s a wonderful art scene, excellent theatre, top class restaurants, and numerous festivals on throughout the year. Someone who is visiting for the first time definitely won’t be stuck for things to do and see. The massive investment in tourism infrastructure in recent years has changed some areas beyond recognition and while the resultant economic growth is of course a positive thing, it’s important to bear in mind that there are large parts of the city that remain deeply divided. Many areas have not benefitted from the regeneration and redevelopment schemes which emerged in the wake of The Good Friday Agreement[2]. In some cases, this focus on the ‘visitor’ and ‘tourist’ tends to be at the expense of those who live in the areas which suffered the most during the Troubles. A prime example of this is the Titanic Quarter and its main attraction, Titanic Belfast, with its adult ticket price of £17.50. Part of their advertising campaign includes the phrase ‘a place for everyone’. A place for everyone, if they have the disposable income to afford it.

If there’s one thing somebody visiting Belfast/NI should see/do/read this year – what would it/they be?

Reading-wise, the book I’m most excited about this year is Lucy Caldwell’s Multitudes, her first short story collection published by Faber and Faber on 5 May 2016, which ‘explores the many facets of growing up — the pain and the heartache, the tenderness and the joy, the fleeting and the formative’ It sounds wonderful. So, people visiting Belfast should go to No Alibis — Belfast’s best bookshop — and buy that. They quite often have signed copies floating around and who doesn’t love a signed copy? And talking of Lucy Caldwell, she has reimagined Chekhov’s Three Sisters for the Lyric Theatre’s Vivid Faces programme (eight plays exploring the nature of identity). It’s set in 1990s Belfast and follows Orla, Marianne and Erin, all disappointed with their lives and dreaming of starting again somewhere new, as they decide if they have the determination to do something about their unhappiness. It opens on 15 October and runs until 19 November 2016 and I have a feeling it’ll be quite special. Actually, all the plays in the Vivid Faces programme sound really interesting, especially Rosemary Jenkinson’s new drama, Here Comes the Night.

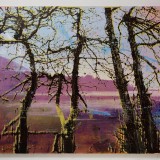

Lough Neagh is beautiful and very peaceful. Anyone visiting Northern Ireland for the first time should definitely add it to their itinerary.

Do you have a favourite place in Belfast/NI?

I moved away from Northern Ireland when I was 18 to go to university in Aberdeen so I’ll pick a childhood favourite. We used to go for a ‘spin in the car’ on Sundays and while I hated the journey (I suffer from very bad motion sickness and R.L. Stevenson was completely wrong — arriving is definitely better than travelling hopefully), I enjoyed the adventure of seeing other places. One of my most vivid memories is of the Sunday we hired a wee boat to tour around Lough Neagh. My father fancied himself as a bit of a boatsman. He didn’t do too badly because it was a very happy day. Lough Neagh is beautiful and very peaceful. Anyone visiting Northern Ireland for the first time should definitely add it to their itinerary.

This isolation from the Troubles changed in August 1998 with the Omagh bomb. I went to school in Omagh and we had been school uniform shopping on the day of the bomb

Your current research is into recent history in Northern Ireland – can you tell us a bit about the catalyst for that, and your experience of living here?

I was very privileged to be isolated from the Troubles where I grew up in rural Tyrone. To me, the Troubles were the odd check-point and the occasional chinook landing in the field opposite our house with a stream of men dressed in green emerging from it. I don’t think I knew what they were doing and I didn’t ask. Looking back now, it’s completely baffling that that was considered ‘normal’ and the fact that I didn’t pay attention to it shows a horrible disregard for the situation in other parts of Northern Ireland. It was as if the things we saw on the news were happening in a different country. This was added to by the fact it was never mentioned in school — another thing that’s completely baffling in hindsight.

This isolation from the Troubles changed in August 1998 with the Omagh bomb. I went to school in Omagh and we had been school uniform shopping on the day of the bomb. We had just left the town to go home when the bomb went off. This, along with a fascinating course on Northern Irish literature during the final year of my undergraduate degree, was the catalyst for my research.

What informs and inspires your work?

Mainly memory studies and trauma theory. Thinkers like Cathy Caruth, Paul Antze, Michael Lambek, Marianne Hirsch, Susannah Radstone, Paul Connerton and Astrid Erll, to name just a few. And scholars who work specifically on Northern Irish memory and cultural production such as Colin Graham, Stefanie Lehner, Caroline Magennis, Shane Alcobia-Murphy and Paula Blair, again, to name just a few.

What are you working on right now?

To cut a long story short, finishing my PhD.

[1] The Troubles refers to a violent thirty-year conflict framed by a civil rights march in Londonderry on 5 October 1968 and the the Good Friday Agreement on 10 April 1998. At the heart of the conflict lay the constitutional status of Northern Ireland. Definition taken from ‘BBC History’ website.

[2] The Good Friday Agreement of 1998 in Northern Ireland, a peace deal that brought an end to the Troubles. Definition taken from ‘BBC History’ website.